Continuous-Time Markov Chains

Iñaki Ucar

2024-09-28

Source:vignettes/simmer-07-ctmc.Rmd

simmer-07-ctmc.Rmd

library(simmer)

library(simmer.plot)

set.seed(1234)Example 1

A gas station has a single pump and no space for vehicles to wait (if a vehicle arrives and the pump is not available, it leaves). Vehicles arrive to the gas station following a Poisson process with a rate of vehicles per minute, of which 75% are cars and 25% are motorcycles. The refuelling time can be modelled with an exponential random variable with mean 8 minutes for cars and 3 minutes for motorcycles, that is, the services rates are cars and motorcycles per minute respectively.

This problem is described by the following continuous-time Markov chain:

$$\xymatrix{ *=<15mm,8mm>[o][F]{car} \ar@/^/[r]^{\mu_\mathrm{c}} & *=<15mm,8mm>[o][F]{empty} \ar@/^/[l]^{p\lambda} \ar@/^/[r]^{(1-p)\lambda} & *=<15mm,8mm>[o][F]{m/cycle} \ar@/^/[l]^{\mu_\mathrm{m}} }\qquad\qquad Q = \begin{pmatrix} -\mu_\mathrm{c} & \mu_\mathrm{c} & 0 \\ p\lambda & -\lambda & (1-p) \lambda \\ 0 & \mu_\mathrm{m} & -\mu_\mathrm{m} \end{pmatrix}$$

with . The chain is irreducible and recurrent. To theoretically find the steady state distribution, we have to solve the balance equations

with the constraint

There are independent columns, so the latter constraint is equivalent to substitute any column by ones and match it to one at the other side of the equation, that is:

The solution represents the probability of being at each state in the long-term. Therefore, we can calculate the average number of vehicles in the system by summing these probabilities multiplied by the number of vehicles at each state. In our case,

# Arrival rate

lambda <- 3/20

# Service rate (cars, motorcycles)

mu <- c(1/8, 1/3)

# Probability of car

p <- 0.75

# Theoretical resolution

A <- matrix(c(1, mu[1], 0,

1, -lambda, (1-p)*lambda,

1, mu[2], -mu[2]), byrow=T, ncol=3)

B <- c(1, 0, 0)

P <- solve(t(A), B)

N_average_theor <- sum(P * c(1, 0, 1)) ; N_average_theor

#> [1] 0.5031056Now, we are going to simulate the system with simmer and

verify that it converges to the theoretical solution. There are various

options for selecting the model. As a first approach, due to the

properties of Poisson processes, we can break down the problem into two

trajectories (one for each type of vehicle), which differ in their

service time only, and therefore two generators with rates

and

.

option.1 <- function(t) {

car <- trajectory() %>%

seize("pump", amount=1) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[1])) %>%

release("pump", amount=1)

mcycle <- trajectory() %>%

seize("pump", amount=1) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[2])) %>%

release("pump", amount=1)

simmer() %>%

add_resource("pump", capacity=1, queue_size=0) %>%

add_generator("car", car, function() rexp(1, p*lambda)) %>%

add_generator("mcycle", mcycle, function() rexp(1, (1-p)*lambda)) %>%

run(until=t)

}Other arrival processes may not have this property, so we would define a single generator for all kind of vehicles and a single trajectory as follows. In order to distinguish between cars and motorcycles, we could define a branch after seizing the resource to select the proper service time.

option.2 <- function(t) {

vehicle <- trajectory() %>%

seize("pump", amount=1) %>%

branch(function() sample(c(1, 2), 1, prob=c(p, 1-p)), c(T, T),

trajectory("car") %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[1])),

trajectory("mcycle") %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[2]))) %>%

release("pump", amount=1)

simmer() %>%

add_resource("pump", capacity=1, queue_size=0) %>%

add_generator("vehicle", vehicle, function() rexp(1, lambda)) %>%

run(until=t)

}But this option adds an unnecessary overhead since there is an

additional call to an R function to select the branch, and therefore

performance decreases. A much better option is to select the service

time directly inside the timeout function.

option.3 <- function(t) {

vehicle <- trajectory() %>%

seize("pump", amount=1) %>%

timeout(function() {

if (runif(1) < p) rexp(1, mu[1]) # car

else rexp(1, mu[2]) # mcycle

}) %>%

release("pump", amount=1)

simmer() %>%

add_resource("pump", capacity=1, queue_size=0) %>%

add_generator("vehicle", vehicle, function() rexp(1, lambda)) %>%

run(until=t)

}This option.3 is equivalent to option.1 in

terms of performance. But, of course, the three of them lead us to the

same result. For instance,

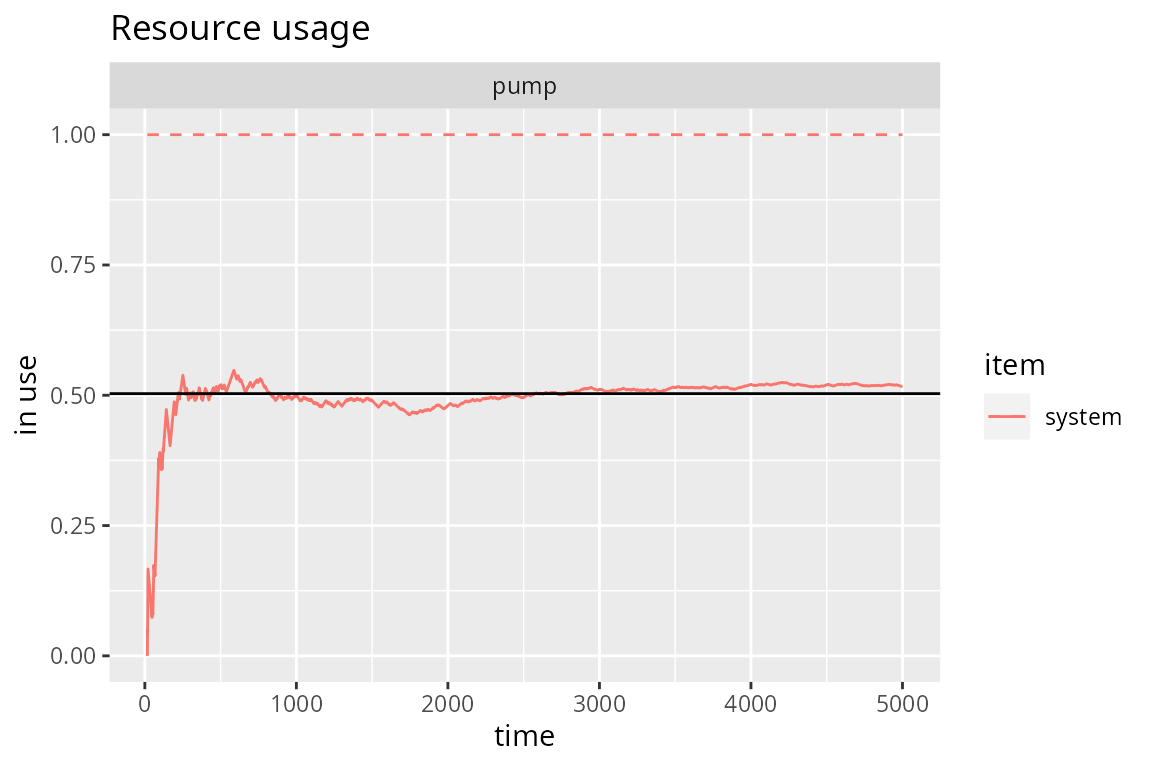

gas.station <- option.3(5000)

# Evolution + theoretical value

plot(get_mon_resources(gas.station), "usage", "pump", items="system") +

geom_hline(yintercept=N_average_theor)

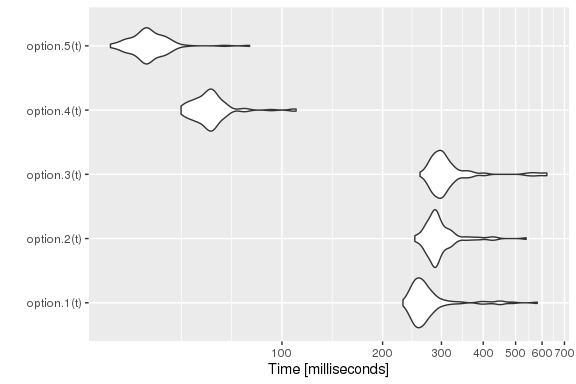

And these are some performance results:

library(microbenchmark)

t <- 1000/lambda

tm <- microbenchmark(option.1(t),

option.2(t),

option.3(t))

autoplot(tm) +

scale_y_log10(breaks=function(limits) pretty(limits, 5)) +

ylab("Time [milliseconds]")

Example 2

Let us complicate things a bit. Consider the previous example, but, this time, there is space for one motorcycle to wait while the pump is being used by another vehicle. In other words, cars see a queue size of 0 and motorcycles see a queue size of 1.

The new Markov chain is the following:

$$\vcenter{\xymatrix{ *=<15mm,8mm>[o][F]{car+} \ar@(r,u)[drr]^{\mu_\mathrm{c}} \\ *=<15mm,8mm>[o][F]{car} \ar@/_/[r]_{\mu_\mathrm{c}} \ar@/^/[u]^{(1-p)\lambda} & *=<15mm,8mm>[o][F]{empty} \ar@/_/[l]_{p\lambda} \ar@/^/[r]^{(1-p)\lambda} & *=<15mm,8mm>[o][F]{m/cycle} \ar@/^/[l]^{\mu_\mathrm{m}} \ar@/_/[d]_{(1-p)\lambda} \\ & & *=<15mm,8mm>[o][F]{m/c+} \ar@/_/[u]_{\mu_\mathrm{m}} }}$$

where the states car+ and m/c+ represent car + waiting motorcycle and motorcycle + waiting motorcycle respectively.

With the steady state distribution, the average number of vehicles in the system is given by

# Theoretical resolution

A <- matrix(c(1, 0, 0, mu[1], 0,

1, -(1-p)*lambda-mu[1], mu[1], 0, 0,

1, p*lambda, -lambda, (1-p)*lambda, 0,

1, 0, mu[2], -(1-p)*lambda-mu[2], (1-p)*lambda,

1, 0, 0, mu[2], -mu[2]),

byrow=T, ncol=5)

B <- c(1, 0, 0, 0, 0)

P <- solve(t(A), B)

N_average_theor <- sum(P * c(2, 1, 0, 1, 2)) ; N_average_theor

#> [1] 0.6349615As in the first example, we can simulate this chain by breaking down

the problem into two trajectories (one for each type of vehicle and

service rate) and two generators. But in order to disallow cars to stay

in the pump’s queue, we need to introduce a little trick in the cars’

seize: the argument amount is a function that

returns 1 if the pump is vacant and 2 otherwise. This implies that the

car gets rejected, because there is only one position in queue and that

seize is requesting two positions. Note also that the

environment env must be defined before

running, as it is needed inside the trajectory.

option.1 <- function(t) {

car <- trajectory() %>%

seize("pump", amount=function() {

if (env %>% get_server_count("pump")) 2 # rejection

else 1 # serve

}) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[1])) %>%

release("pump", amount=1)

mcycle <- trajectory() %>%

seize("pump", amount=1) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[2])) %>%

release("pump", amount=1)

env <- simmer() %>%

add_resource("pump", capacity=1, queue_size=1) %>%

add_generator("car", car, function() rexp(1, p*lambda)) %>%

add_generator("mcycle", mcycle, function() rexp(1, (1-p)*lambda))

env %>% run(until=t)

}The same idea using a branch, with a single generator and a single trajectory.

option.2 <- function(t) {

vehicle <- trajectory() %>%

branch(function() sample(c(1, 2), 1, prob=c(p, 1-p)), c(F, F),

trajectory("car") %>%

seize("pump", amount=function() {

if (env %>% get_server_count("pump")) 2 # rejection

else 1 # serve

}) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[1])) %>%

release("pump", amount=1), # always 1

trajectory("mcycle") %>%

seize("pump", amount=1) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[2])) %>%

release("pump", amount=1))

env <- simmer() %>%

add_resource("pump", capacity=1, queue_size=1) %>%

add_generator("vehicle", vehicle, function() rexp(1, lambda))

env %>% run(until=t)

}We may also avoid messing up things with branches and

subtrajectories. We can decide the type of vehicle and set it as an

attribute of the arrival with set_attribute(). Then, those

attributes can be retrieved using get_attribute(). Although

the branch option is a little bit faster, this one is nicer, because

there are no subtrajectories involved.

option.3 <- function(t) {

vehicle <- trajectory("car") %>%

set_attribute("vehicle", function() sample(c(1, 2), 1, prob=c(p, 1-p))) %>%

seize("pump", amount=function() {

if (get_attribute(env, "vehicle") == 1 &&

env %>% get_server_count("pump")) 2 # car rejection

else 1 # serve

}) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[get_attribute(env, "vehicle")])) %>%

release("pump", amount=1) # always 1

env <- simmer() %>%

add_resource("pump", capacity=1, queue_size=1) %>%

add_generator("vehicle", vehicle, function() rexp(1, lambda))

env %>% run(until=t)

}But if performance is a requirement, we can play cleverly with the

resource capacity and the queue size, and with the amounts requested in

each seize, in order to model the problem without checking

the status of the resource. Think about this:

- A resource with

capacity=3andqueue_size=2. - A car always tries to seize

amount=3. - A motorcycle always tries to seize

amount=2.

In these conditions, we have the following possibilities:

- Pump empty.

- One car (3 units) in the server [and optionally one motorcycle (2 units) in the queue].

- One motorcycle (2 units) in the server [and optionally one motorcycle (2 units) in the queue].

Just as expected! So, let’s try:

option.4 <- function(t) {

vehicle <- trajectory() %>%

branch(function() sample(c(1, 2), 1, prob=c(p, 1-p)), c(F, F),

trajectory("car") %>%

seize("pump", amount=3) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[1])) %>%

release("pump", amount=3),

trajectory("mcycle") %>%

seize("pump", amount=2) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[2])) %>%

release("pump", amount=2))

simmer() %>%

add_resource("pump", capacity=3, queue_size=2) %>%

add_generator("vehicle", vehicle, function() rexp(1, lambda)) %>%

run(until=t)

}We are still wasting time in the branch decision. We can

mix this solution above with the option.1 to gain extra

performance:

option.5 <- function(t) {

car <- trajectory() %>%

seize("pump", amount=3) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[1])) %>%

release("pump", amount=3)

mcycle <- trajectory() %>%

seize("pump", amount=2) %>%

timeout(function() rexp(1, mu[2])) %>%

release("pump", amount=2)

simmer() %>%

add_resource("pump", capacity=3, queue_size=2) %>%

add_generator("car", car, function() rexp(1, p*lambda)) %>%

add_generator("mcycle", mcycle, function() rexp(1, (1-p)*lambda)) %>%

run(until=t)

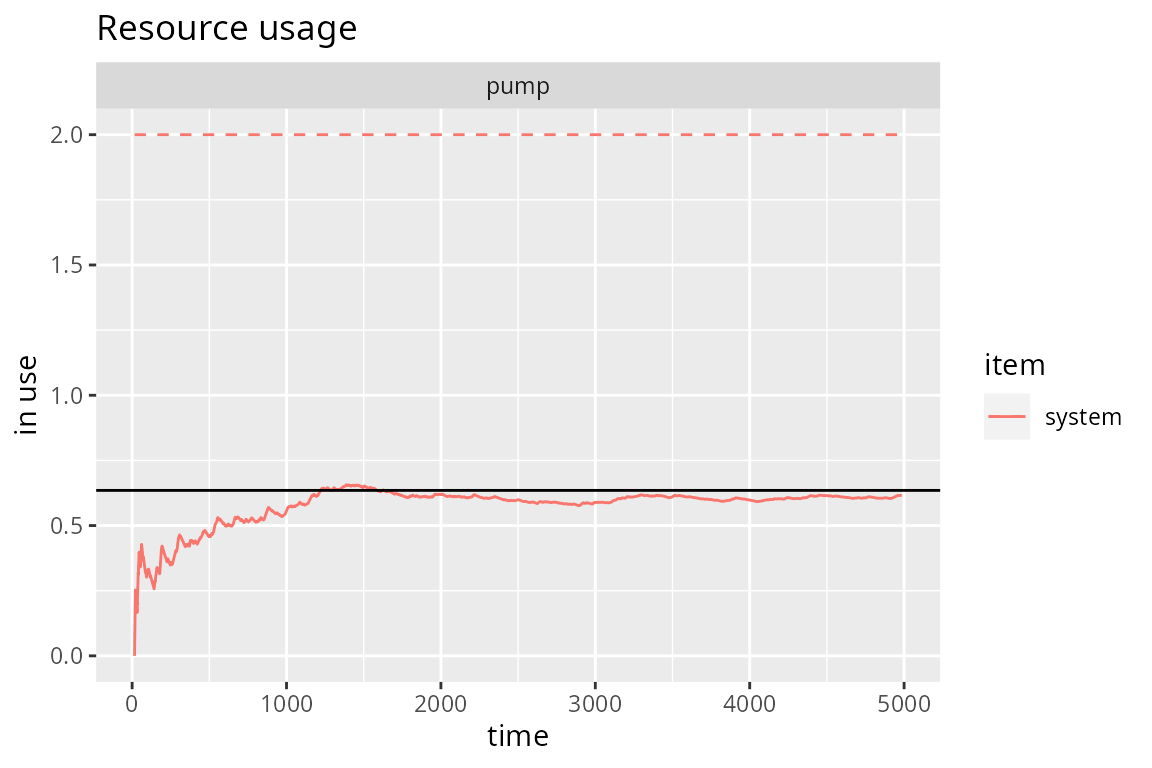

}Options 1, 2 and 3 are slower, but they give us the correct numbers, because the parameters (capacity, queue size, amounts) in the model remain unchanged compared to the problem. For instance,

gas.station <- option.1(5000)

# Evolution + theoretical value

plot(get_mon_resources(gas.station), "usage", "pump", items="system") +

geom_hline(yintercept=N_average_theor)

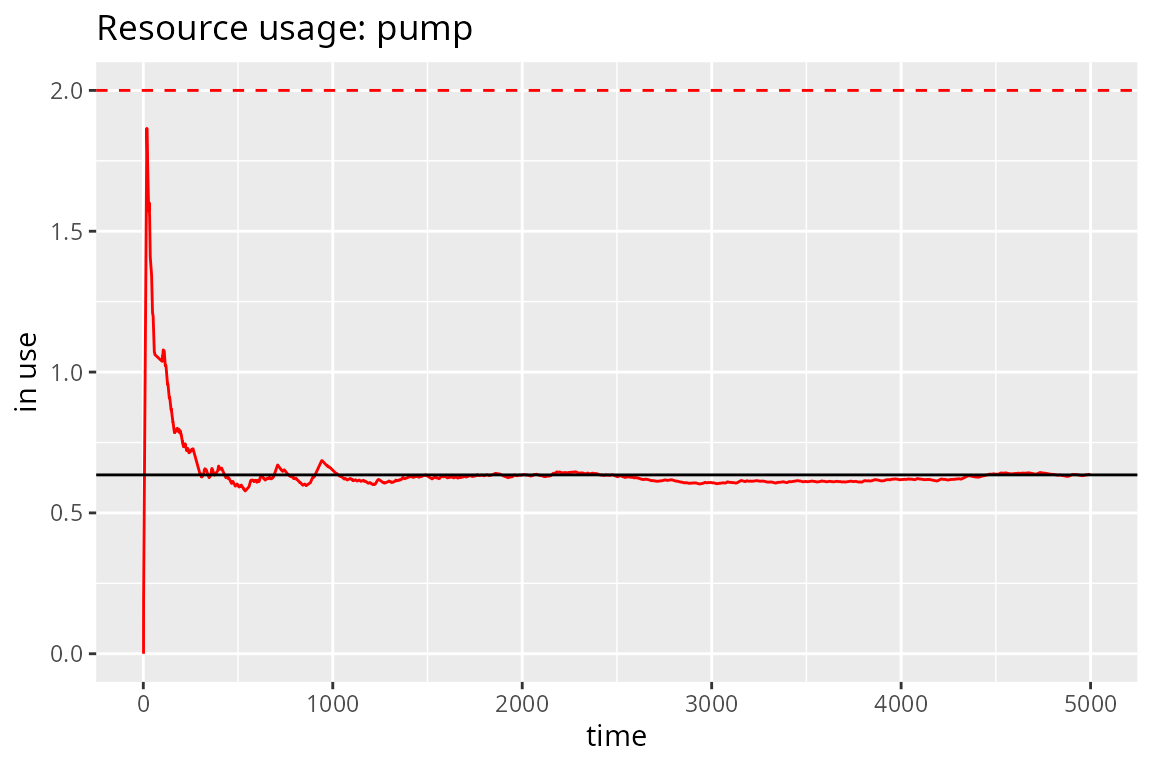

However, it is not the case in options 4 and 5. The parameters of these models are adulterated to fit our performance purposes. Therefore, we need to extract the RAW data, rescale the numbers and plot them. And, of course, we get the same figure:

gas.station <- option.5(5000)

get_mon_resources(gas.station) %>%

transform(system = round(system * 2/5)) %>% # rescaling

transform(avg = c(0, cumsum(head(system, -1) * diff(time))) / time) %>%

ggplot(aes(time, avg)) + geom_line(color="red") + expand_limits(y=0) +

labs(title="Resource usage: pump", x="time", y="in use") +

geom_hline(yintercept=2, lty=2, color="red") +

geom_hline(yintercept=N_average_theor)

Finally, these are some performance results:

library(microbenchmark)

t <- 1000/lambda

tm <- microbenchmark(option.1(t),

option.2(t),

option.3(t),

option.4(t),

option.5(t))

autoplot(tm) +

scale_y_log10(breaks=function(limits) pretty(limits, 5)) +

ylab("Time [milliseconds]")